Last week noticed the American DVD launch of “Gerry Anderson: A Life Uncharted” (MPI Home Video), a brand new documentary on the British producer, author and director greatest recognized right here as the man behind “Thunderbirds,” the Nineteen Sixties slow-action puppet journey present — “filmed in Supermarionation” — and, amongst viewers of a sure age (or inclination), for its predecessors “Supercar,” “Fireball XL5” and “Stingray.” Boy and man, I was and am a fan of those fanciful sequence, which aren’t like anything tv has ever supplied, and which, together with later highlights and midlights of Anderson’s profession (which lasted in matches and begins into the twenty first century), are nonetheless in circulation, a decade after Anderson’s demise in December 2012, on residence video and to stream, legally and in any other case. Some have lived on by way of novels, comics, soundtrack albums, radio dramas, mannequin kits and motion figures; thus far, there are almost 250 episodes of the cheery, cheeky “The Gerry Anderson Podcast,” co-hosted by youngest son Jamie Anderson. Anytime is the time to climb on board this atomic prepare.

The Tracy household and allies of International Rescue, the heros of the futuristic “Supermarionation” tv present Thunderbirds. Seated, heart, is father Jeff Tracy. He is surrounded by (from left to proper) John Tracy, Lady Penelope, Scott, Alan, and Gordon Tracy, and (seated) Tin-Tin, Virgil Tracy, and Brains.

(Hulton Deutsch/Corbis through Getty Images)

None of Anderson’s sequence lasted greater than a season or two (not even the flagship “Thunderbirds,” although it additionally produced two theatrical options). But this turnover meant that quite a lot of applications, a number of co-credited to second spouse Sylvia Anderson — a credit score Anderson regretted, together with the marriage itself, however which different collaborators say was deserved — had been delivered to fruition. These included the live-action “Space: 1999,” with Martin Landau and Barbara Bain, through which Moonbase Alpha and the moon itself go hurtling into deep area after a nuclear explosion, and the post-“U.N.C.L.E.” Robert Vaughn international detective show “The Protectors,” which were syndicated in America, and “Space Precinct,” with Ted Shackelford as a former NYPD lieutenant fighting crime on the planet Altor, which was not. There was the sci-fi drama “Terrahawks,” with its Muppet-style puppets, and the stop-motion fantasy “Lavender Castle.” But marionettes are what made him.

Space 1999, Science Fiction TV Series, filmed at Pinewood Studios, Iver Heath, Buckinghamshire, 25th September 1999. The series ran for two seasons. Starring Barbara Bain as Doctor Helena Russell and Martin Landau as Commander John Koenig.

(Mirrorpix/Mirrorpix via Getty Images)

Television’s first puppet superstar was a marionette, Howdy Doody. There are advantages to that sort of figure — you can frame them from head to toe, place them bodily into a set. But where a hand in a sock can become something quite expressive and convincingly alive, marionettes, with their knees-up walk, their floating arms and bobbing heads, their fairly fixed expressions and utter lack of dexterity, have to work hard to seem at all natural. But those limitations also determined the structure of Anderson shows, which feature moving sidewalks, hovering chairs and scooters and place the characters in cockpits and at consoles, putting the emphasis on the materiel, the aircraft and submarines and super-cars, the impressive sets and miniatures — blown up or set afire with satisfying regularity. They used the tools of cinema — lighting, camera movement and angles, and clever editing — to make something new and unpredictable.

Anderson, who had entered the film business as an editor, backed into puppet television when the fledgling production company in which he was a partner made a commercial for the British equivalent of Rice Krispies, featuring a marionette version of Noddy, a popular children’s book character. It led to two shows commissioned by author Roberta Leigh, “The Adventures of Twizzle” and “Torchy, the Battery Boy” (whose theme song the Beatles were said to play at the Cavern), followed by a marionette western, “Four Feather Falls,” which introduced a voice-activated solenoid to move the puppets’ lower lips.

This was all preamble. The Anderson oeuvre proper begins in 1961 with “Supercar,” about a nifty land-sea-air vehicle (“It travels in space and under the sea/ And it can journey anywhere,” according to its theme song), whose pilot bears a coincidental resemblance to Eugene Levy. It began Anderson’s relationship with Lord Lew Grade, who would habitually greenlight his projects until the executive’s own power failed. “Fireball XL5,” a space opera, was next, and then “Stingray,” essentially an underwater “Fireball XL5” and the first Anderson production (and British program) to be made in color.

Then came “Thunderbirds,” in 1965, the work for which Anderson is most celebrated. If his science-fiction shows had been all about the machines — each was titled after the vehicle at its center — “Thunderbirds” offered five, count ’em, five big craft (and a host of smaller diggers and bulldozers), tooled to accomplish large-scale rescue operations — their enemies were industrial accidents, natural disasters and sabotage — plus a six-wheeled futuristic pink Rolls-Royce. Operations were run from the stylish Midcentury Modern island headquarters of International Rescue, home to chief Jeff Tracy and his five sons, all named for Project Mercury astronauts. (The Cartwrights of “Bonanza” were an inspiration.) As in earlier Anderson productions, the main characters were made American, the better to penetrate our insular market. (The Rolls belonged to the Tracys’ British associate, the aristocratic, glamorous Lady Penelope, played by Sylvia Anderson; comical Cockney chauffeur Parker, played by David Graham — also known as the voice of “Doctor Who’s” Daleks — was at the wheel.)

These shows evince a house style as quickly identifiable, domestically speaking, as the candy-colored, costumed fever dreams of Sid and Marty Krofft — the team behind “H.R. Pufnstuf” and “Sigmund and the Sea Monsters” — or the stop-motion holiday specials of Arthur Rankin and Jules Bass. But for a generation of Britons, they were even more culturally potent. The crafts and characters and catchphrases permeated the national consciousness; the vehicle-stars were, and for some incalculable segment of the public are, as familiar in silhouette as the James Bond Aston Martin, the “Star Trek” Enterprise, the Batmobile, the TARDIS.

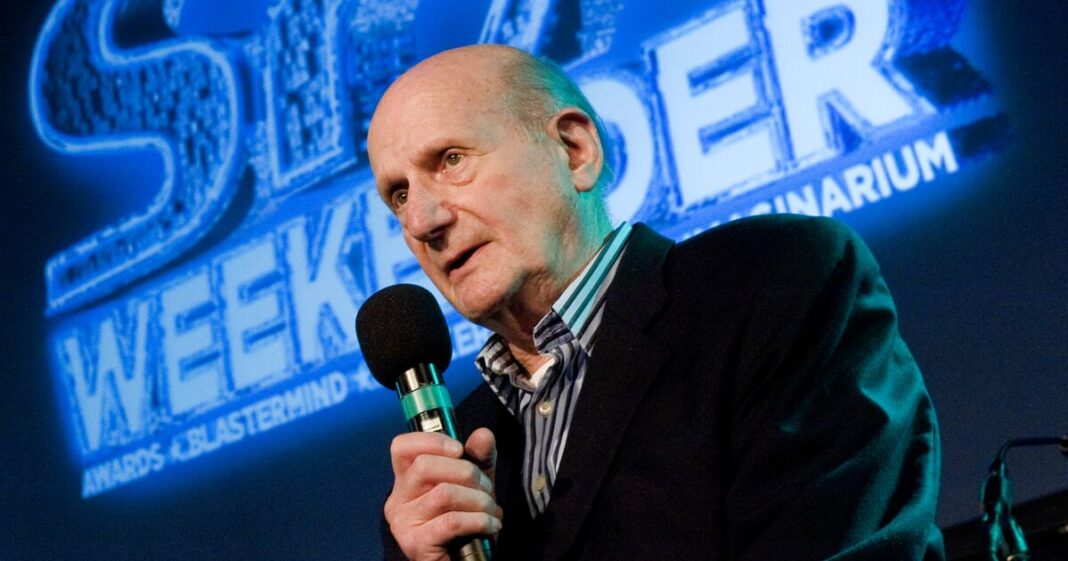

Gerry Anderson, the man behind some of the great television shows, launches, with the help of Captain Podley, a range of toys taken from his new sci-fi series Space Precinct. The toys went on sale in Hamleys, Regent Street, London, and cost between 3.99 and 34.99.

(Michael Stephens – PA Images/PA Images via Getty Images)

The big heads of the early Anderson puppets were determined by the mechanics that controlled their lips; technological developments made it possible to produce marionettes with heads proportional to their bodies, which produced something even weirder. The characters of “Captain Scarlet and the Mysterons” (color-coded heroes, one of them virtually immortal, versus Mars-based aliens), “Joe 90” (9-year-old boy practices espionage when brainwaves of adult experts are piped into his head) and “The Secret Service” (vicar-spy shrinks associate, who is also his gardener, to doll size for doll-size missions) can come off something like a convention of Kens and the occasional Barbie. The cognitive dissonance is something like the “uncanny valley” that afflicts digitally created human characters. It’s easier to bring persuasive life to a digital caricature than to a presumably realistic human. Ironically — unavoidably, one might even say — Anderson’s last series was the 2005 CGI revival of “Captain Scarlet.”

Newsletter

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for all the things about the TV reveals and streaming motion pictures everybody’s speaking about.

You could often obtain promotional content material from the Los Angeles Times.

Although Anderson described being “embarrassed” by working with puppets — he would have most well-liked to direct typical movies — it led him consequently to attempt for better realism in his productions, and to deal with extra grownup tales and themes. It was this ambition, and its limits, that kind the coronary heart of his legacy. What makes his reveals completely great is the means through which their attain exceeds their grasp; they’ll by no means be naturalistic, although they’re solely actual. Even as you give up your self to the story, you’re conscious of the artifice, the artwork and craft and invention that went into creating these worlds. Delightful particulars fill the display — these are reveals not merely to observe however to have a look at. A “Thunderbirds” film from 2004 starring Bill Paxton and Ben Kingsley, with a Hans Zimmer rating, is technically unimpeachable however not almost as attention-grabbing as the puppet present, with its usually seen strings and handmade have an effect on.

Directed by Benjamin Field, “Gerry Anderson: A Life Uncharted” presupposes a familiarity with Anderson’s work, which is seen solely in short clips to remark sarcastically on his life. But it has loads to advocate it as a narrative of the British tv trade in the twentieth century, a turbulent private drama and an examination of the means through which even sad private expertise could also be transmuted into interesting well-liked artwork. (Hours of behind-the-scenes documentaries, if that’s what you’re after, could also be discovered on the official Gerry Anderson YouTube channel, and elsewhere.) Jamie Anderson, the product of his father’s third (and ultimately profitable) marriage, is its quasi-narrator, on a journey to grasp a father who “produced 18 series and four feature films, owned six Rolls-Royce motor cars, had three children across three marriages and made and lost his fortune twice over,” however who in some ways remained a thriller to him. (Anderson speaks for himself right here, with some “deep fake” visuals to accompany tape-recorded interviews.)

He was the product of an sad marriage — his father was Jewish his mom antisemitic, in case you can think about — whose idolized older brother was an RAF pilot killed in the Second World War. (His mom instructed him she wished it had been Gerry who died, a sentiment Anderson himself distressingly echoes.) That Anderson discovered success making reveals about heroic pilots is some extent not left unmade, neither is the incontrovertible fact that moms are considerably absent from his sequence. In the finish, it was all moot. Alzheimer’s illness erased each the trauma and triumphs from his reminiscence, if not from the public’s. An overflow crowd attended his funeral, and a flower association in the form of the large inexperienced Thunderbird 2 sat atop his casket.